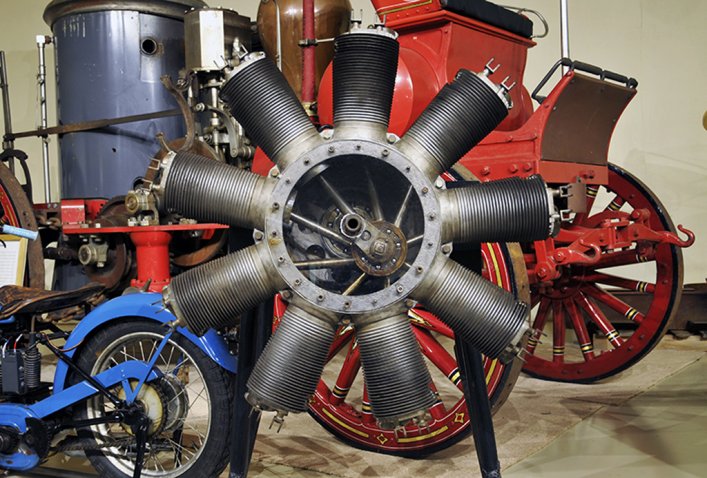

1917 Clerget 9B

Description

The defining feature of a rotary engine is the entire engine spins as it operates. The propeller is mounted to the front of the crankcase and the combination revolves around a fixed crankshaft. Between 1909 and 1920, the rotary engine provided a favorable power to weight ratio compared to other aircraft engines on the market. As an air-cooled engine, the weight of a radiator, coolant, and all the connecting pipes and hoses was eliminated. The rotating operation of…

The defining feature of a rotary engine is the entire engine spins as it operates. The propeller is mounted to the front of the crankcase and the combination revolves around a fixed crankshaft. Between 1909 and 1920, the rotary engine provided a favorable power to weight ratio compared to other aircraft engines on the market. As an air-cooled engine, the weight of a radiator, coolant, and all the connecting pipes and hoses was eliminated. The rotating operation of the engine, coupled with a total loss lubrication system (where the oil flows through the engine and immediately lost through the exhaust valves) provided additional cooling benefits.

This oiling system was also largely responsible for the signature pilot’s outfit of World War I of the scarf and goggles. The goggles helped keep oil flung from the engine out of the pilot’s eyes while the scarf meant the pilot always had an available cloth to clean the oil off his goggles. The scarf was also a useful mask from inhaling or absorbing the oil. Castor oil was often used in rotary engines due to its outstanding lubricating qualities but is also a powerful laxative.

The Clerget 9B was first manufactured in 1911, but was still a successful design for World War I. Due to the rotary design, the Clerget produces more power and weighs less than the Hall-Scott engine on display. During World War I, thousands of Clerget 9B engines were built and used on over a dozen French and British aircraft, including the Nieuport 17.